Young Children’s Voices in Mathematical Problem Solving

Contributed by Dr Ho Siew Yin and Sng Wei Qin Abbie, from NTUC First Campus, for SingTeach Virtual […]

Read More

These case studies are offered as starting points for teachers to access instances of AfL in the local context and adapt ideas into their own classrooms.

As the Singapore educational landscape continues to strive towards a more balanced assessment system, schools are turning to Assessment for Learning (AfL) to complement the practice and influence of summative assessment. This is particularly important with recent policy initiatives such as the restriction in the number of weighted assessments in Singapore schools and advancing teacher’s assessment literacy.

These case studies are offered as starting points for teachers to access instances of AfL in the local context and adapt ideas into their own classrooms. They illustrate how AfL can and should be adapted in different subject and classroom contexts.

The research team worked with four secondary school teachers (teaching English, Geography, Math and Science) to review their lessons. We wanted to focus on the secondary school context as we noted there are more known examples of AfL practices in the primary school context. It has also been reported in literature that secondary school teachers have encountered more difficulties in enacting AfL (McMillan, 2010).

In this research, secondary school teachers were interviewed and comments were given on their lesson plans to help them think further about incorporating AfL process (see framework below). Subject specific issues were also surfaced and discussed, with help from the consultants who were experts in the different subjects. The team observed and video-recorded the teachers’ lessons and conducted a review. A lesson package comprising a video clip, resources and handout was then created from the data collected.

Lesson plans and resources from eight other teachers were also reviewed to give a more general view of how teachers understand and carry out AfL. Although these teachers were not video-recorded or interviewed formally, insights gleaned helped provide a clear picture of how AfL was enacted as well as suggest subject-specific issues.

An earlier research on perceptions, policies and practices of AfL in 13 secondary schools (Leong et al., 2019) suggested that:

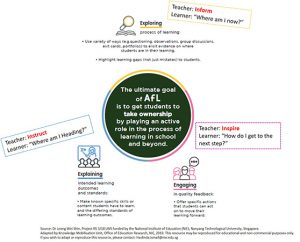

Hence, a framework was developed by the research team to guide teachers towards a more learner-centred AfL process that aimed for achieving broader learning outcomes (see Figure 1). We believe such deliberate re-orientation will support student’s life-long learning endeavours.

Figure 1: Framework of Learner-Centred AfL Process ( view larger image )

(more research findings on AfL can be found here:https://sites.google.com/view/ctl-assessment/AfL)

The framework emphasised AfL as an iterative process that can have different starting points, with the ultimate goal of enabling students to take ownership of their learning. For instance, it is typical in the beginning of a sequence of teaching-learning of a topic, to help students to understand clearly ‘Where am I Heading?’ through explaining learning objectives, discussing rubrics and students’ artifacts. In such a stage of AfL, teachers are likely to take on a more instructive role of modelling successful learning for instance. In the later stages, the role of teachers in AfL should evolve to a more informing and inspiring one, for instance to allow students to discuss ‘Where Am I Now?’ and ‘How Do I Get to Next Step?’. Such a framework complements well-known AfL framework (e.g. Wiliam and Leahy, 2015) by emphasizing AfL as not just a set of strategies or IT tools (e.g. using ‘traffic lights’ or using ‘Kahoot’), but also intentional (subject-general) process that supports learning. The lessons and resources designed in this project make use of this framework.

What Studies Say about Differences in AfL across Subjects

Studies have also shown that there may be differences in how AfL is actualised across subjects (Hodgen & Marshall, 2005; Marshall, 2007). The differences are typically found between the Arts (English Language and the Humanities) and the Sciences (Maths and Science). AfL process in the Arts tend to develop and widen students’ thinking more and interventions are often impromptu. AfL process in the Sciences, on the other hand, tend to be diagnostic in nature, meant to identify and close a specific learning gap (Marshall, 2007). One possible reason could be how the subjects have historically been taught, with the teaching of Arts and Humanities traditionally rooted in the socio-cultural/constructivist and the Maths and Sciences in the cognitive, constructivist theories of learning (Hodgen & Marshall, 2005).

Due to the varying levels of assessment literacy among the teachers, some teachers might carry out Assessment for Learning (AfL) without consciously realizing that they were doing so. Nevertheless, most of them seemed to understand that AfL help bridge what teachers taught with what students learned. Teachers constantly moved between the AfL process of “Explaining”, “Exploring” and “Engaging” as the lesson moved along.

An activity could also simultaneously reflect different stages overlapping. For example, a teacher could explore what students understood about the expected standards of a task by asking questions. At the same time, he/she could explain in greater detail what those expected standards were even as he/she asked these questions. The teachers observed not only carried out the three AfL stages iteratively, they did so in a non-linear fashion.

We also noted the AfL process of “Explaining”, “Exploring” and “Engaging” need not be conducted solely by the teacher but should involve student’s initiations as well. In many cases, AfL offered opportunities for greater student engagement, for example, students can “Explain” the success criteria for a given task to each other. Different students benefitted from starting, overlapping and emphasizing different stage of this process.

Videos of Enacted AfL Process

Videos of the enacted AfL process across different subjects can be found below. Accompanying materials and some subject-specific concerns, as suggested by subject experts, are also detailed.

| Enacted AfL Lessons | Videos | Accompany Materials | Feedback from Consultants/Research team: |

|---|---|---|---|

| English Language Lesson (Sec 2) with Mr Alfred Liu Hao Wei of Woodlands Ring Secondary School | Many good attempts to give opportunities for students to assist each other. There is a tension of the teacher still wanting students to be able to respond according to summative assessment requirements (only), rather than focusing on skills and competency. | ||

| Geography Lesson (Sec 3) with Ms Aruna Govind of Woodlands Ring Secondary School | Potentially, AfL can help to bridge different sub-topics together for a more thorough discussion. | ||

| Mathematics Lesson (Sec 3) with Ms Lynn Yeo of Mayflower Secondary School | Asking the right questions goes a long way in accurately assessing where students are in their learning and in surfacing misconceptions. | ||

| Science Lesson (Sec 3) with Ms Jeevana Rani of Mayflower Secondary School | Pre-empting students’ misconceptions will help teachers address them when students encounter them. |

Table 1: Videos of enacted AfL process in different subjects

The understanding of AfL process and proficiency in carrying them out differed from teacher to teacher. As such, after reviewing their lesson plans with the research team, each teacher might have revised their lesson plans in different ways. More details of the changes made to the lessons could be found in the handouts accompanying the videos. Some of the changes made were:

Teachers need to understand how to adapt AfL process in different lessons and student contexts. We hope that the four case studies will help teachers to have a starting point on this. They should not be apologetic about ‘taking time’ for students to learn in lessons. Neither should they feel guilty about ‘switching into’ an examination preparation mode occasionally.

We agree with Carless (2010) and McMillan (2010) who have suggested that AfL could be thought of not as a single entity in the classroom but rather as a family of practices that differed in certain characteristics or levels of formative-ness in different types of classrooms (see Table 2). We also propose that an explicit embedding or linking of AfL process to Singapore Teaching Practice (STP) framework can help teachers to make sense of the essential connectivity of teaching areas that are already highlighted in the framework. Indeed, such a connectivity exemplify how AfL is the essential bridge between teaching and learning in the everyday classroom context.

| Characteristics | High-level Formative | Low-level Formative |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence of student learning (Refer to STP’s Pedagogical Practice: Lesson Preparation) | Varied assessment items, from objective (standardized) to anecdotal (self-selected) | Mostly objective (standardized) assessment items |

| Participants involved/Choice of task (Refer to STP’s Pedagogical Practice: Lesson Preparation) | Teacher and students-directed | Teacher-directed |

| Instructional adjustments (Refer to STP’s Pedagogical Practice: Lesson Enactment) | Highly flexible and attending to individual students in-situ | Highly scripted and delayed |

| Feedback (Refer to STP’s Pedagogical Practice: Assessment and Feedback) | Immediate and specific for low-progress students, delayed for high progress students | Mostly delayed for all students |

| Role of student self-assessment (Refer to STP’s Pedagogical Practice: Assessment and Feedback) | Integral | None or minimal |

| Motivation (Refer to STP’s Pedagogical Practice: Positive Classroom Culture) | Intrinsic | Extrinsic (do well for exam only) |

| Classroom culture (Refer to STP’s Pedagogical Practice: Positive Classroom Culture) | Informal, interactive and safe haven for making mistakes | Formal and competitive |

Table 2: Variations of formative assessment characteristics (Adapted from McMillan, 2010, pg. 43)

According to Table 2, AfL can vary according to how each characteristic is defined and put into a process of classroom practices. At one end, of this continuum, low-level formative assessment resembles summative assessment, but yet there could be important learning out of even such a context (e.g. being careful, time management etc.). We propose however this is considered only low-level formative assessment. On the other end, the focus is on individual student’s learning and the emphasis could be more on developing student dispositions through self-assessing activities, focusing on intrinsic motivation and building a culture where mistakes can be made and learnt from. We need to see more examples of this, and the four case studies in this project illustrate the possibilities and also room for improvements. We recommend that high-level formative assessment (that is not just aligned to exam performance) can be more widely practised across Singaporean schools.

School leaders and key personnel should assist their teachers by to understand that the essence of AfL process can be evident through the different Pedagogical Practices in STP as already noted in Table 2 above. Providing an organisational assessment planning frame that goes beyond ‘curriculum coverage’ (and summative assessment weightings) will afford their students and themselves, more sophisticated attention to different AfL that can be possible in different lessons. Subject and assessment specialists and researchers should work in tandem to help teachers identify full range of learning evidence, such that an inclusive range of student’s achievement and learning progress can be discerned differentially through appropriate assessment practices.

Some further points to ponder:

Tay, H. Y. (2019, July 5). Assessment for Learning (AfL): It’s all about the students and their learning. [Video clip]. Retrieved from https://www.nie.edu.sg/news-detail/assessment-for-learning-(afl)-it-s-all-about-the-students-and-their-learning

To learn more about the AfL project, please contact Ms Haslinda Ismail at Haslinda.Ismail@nie.edu.sg or oerkmob@nie.edu.sg.

Principal Investigator

Dr Leong Wei Shin, MOE (formerly of NIE)

Consultants

Dr Dorothy Tricia Seow Ing Chin, Humanities & Social Studies Education (HSSE)

Research Associate

Ms Haslinda Bte Ismail (formerly of NIE)

Intern

This study was funded by the National Institute of Education (NIE), Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (RS 3/18 LWS). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of NIE.

Research was conducted under auspices of institutional review board reference IRB-2018-10-061.

This knowledge resource was written by Dr Leong Wei Shin and Ms Haslinda Bte Ismail with minor inputs from Ms Tan Giam Hwee in February 2020; updated by Ms Monica Lim and Mr Jared Martens Wong on 11 January 2022.