Young Children’s Voices in Mathematical Problem Solving

Contributed by Dr Ho Siew Yin and Sng Wei Qin Abbie, from NTUC First Campus, for SingTeach Virtual […]

Read More

Contributed by Chua Wan Yu from Temasek Secondary School and Dr Tricia Seow from the National Institute of Education, for SingTeach Virtual Staff Lounge

Engaging students in climate change education can be challenging, particularly when its impacts are not immediately tangible. In Singapore, while students may relate to terms like “global warming” and “carbon dioxide,” fostering a deeper understanding and actionable responses often proves difficult due to the abstract nature of the topic and its overwhelming content. So, how can we make this critical topic more engaging and relatable? This study investigates the use of gamification as a pedagogical strategy to enhance conceptual learning about climate actions. It looks at how a climate-policy-focused card game, “Getting to Zero”, has significantly improved students’ awareness of climate policies, comprehension of trade-offs in policymaking, and motivation to engage with climate solutions.

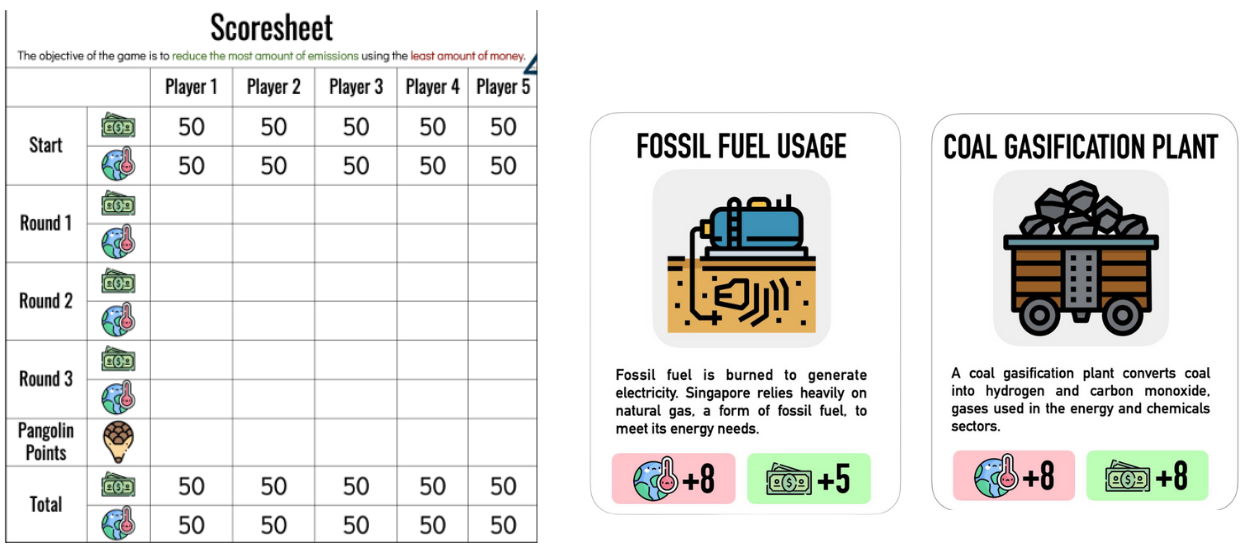

Photos: The gameplay of the “GTZ” card game

Deterding (2011) defines gamification as integrating game elements into non-game contexts to enhance engagement and motivation, emphasizing that thoughtful design, rather than superficial rewards, sustains long-term learning outcomes. Kapp (2012) explores practical applications, demonstrating how game mechanics can simplify complex concepts and foster active learning. Both researchers stress that effective gamification can be a powerful tool to motivate students’ learning. Their research underscores how gamification can promote active participation and knowledge transfer, making abstract concepts accessible and memorable. Together, their findings emphasize thoughtful gamification as a transformative educational tool.

In the context of using gamification to engage students on climate issues, researcher Carrillo-Nieves et al. (2024) explored gamification through designing station games, including escape rooms, and engaging undergraduates in combating climate change by fostering problem-solving and collaboration. Using gamification as a pedagogical strategy in Geography classrooms is an area that remains largely unexplored, especially within Singapore’s education landscape.

This begs the question of whether a climate-policy-focused card game such as “Getting to Zero” (GTZ) can significantly enhance students’ awareness of climate policies and lead students to develop a deeper understanding of the complexities faced by nations in climate policymaking.

GTZ was introduced to a group of 36 Secondary Three students from the G2 level as part of their Geography lesson on climate action. It was intentionally used as a trigger to activate prior knowledge and engage students with the subject matter. A pre- and post-survey was administered to measure students’ knowledge, contextual understanding, and interests toward the topic on climate. Quantitative survey items used a Likert scale (1 to 5) for self-assessment, while qualitative questions encouraged students to articulate their learning experiences from the game.

Students had a better understanding of climate policies after engaging with the card game. Their self-assessments highlighted increased awareness of “trade-offs”, a concept integrated into the game’s strategy for winning and a critical concept highlighted within the Geography curriculum. Additionally, students reported a greater understanding of how individual actions could contribute to reducing their climate impact.

Question: “I am clear about what Getting to Zero means”. The positive response to this question demonstrated that students had a clear understanding the importance of achieving a net-zero carbon footprint as a climate action strategy. This mirrors real-life efforts, where authorities implement climate policies to balance emissions with reductions.

Questions: “I know the purpose of implementing climate policies in Singapore” & “I know the constraints Singapore faces when implementing climate policies”. The positive responses to these questions demonstrated that students had a foundational understanding of why countries, including Singapore, take action through climate policies. Their grasp of the constraints highlighted an awareness that implementing climate actions is far from straightforward. Students recognized that numerous considerations and competing priorities—many of which they encountered during the game—can deter countries from taking immediate or extensive action.

Question: “I know at least 3 climate policies”. This survey question revealed an increase in responses at the lower levels of understanding and a reduction in responses at the higher levels. This question, which required students to list three climate policies, appeared more demanding due to the specific and quantitative nature of the task. While this may signal the lack of retention for some students, it was also noted that some students overly strategized to win the game, neglecting the details presented in the card game.

To address this, teachers need to facilitate effectively by ensuring sufficient time for students to consider and articulate their moves during the game. Additionally, providing opportunities for post-game discussions will allow students to reflect on their strategies and the climate actions they have taken, deepening their understanding of the decision-making process and facilitating the retention of content knowledge.

An analysis of the vocabulary used in students’ reflections indicated mastery of critical content, such as “carbon emissions,” a central element of the game’s mechanics where players aimed to reduce net emissions to zero. Many students articulated the complexities of trade-offs, describing balancing costs while achieving emission reductions as a “downside” in policymaking (see Appendix A). These findings underscore the game’s effectiveness in fostering both engagement and conceptual understanding.

Other qualitative feedback from students revealed insights into their self-assessed interest levels regarding climate-related issues. Many students expressed increased curiosity and a desire to contribute positively to reducing carbon emissions in Singapore. Comments highlighted an awareness of local efforts, such as the government’s use of solar panels, and a personal commitment to reducing their carbon footprint. One student commented “The game was very engaging and educational, and made me more curious on the different type of ways to reduce carbon emissions”.

On gauging the interest level of the topic, qualitative feedback from students expressed the fun element while playing the card game, making the topic more relatable. These responses illustrate how the gamified approach effectively captured the interest of most students, fostering a sense of individual responsibility and curiosity about climate actions.

Overall, the card game proved effective in promoting the understanding of conceptual knowledge within the climate issues and fostering engagement which answers to our action research question. However, it is also important to recognize its limitations. The game is not a foolproof solution or a magical tool that can fully address all learning objectives. Certain aspects, such as the retention of specific content like climate policies, were less successful as some students struggled with the recall tasks or became overly focused on winning rather than absorbing detailed knowledge.

Additionally, the game’s design may not cater equally well to all students, particularly those who require additional scaffolding or alternative approaches to grasp complex concepts. These limitations highlight the need to view the card game as a complementary tool within a broader pedagogical strategy, rather than as a standalone solution.

The game can serve as both a trigger and a reinforcement tool in the learning process. As a trigger, it activates students’ prior knowledge while introducing new information, sustaining their attention and sparking interest at the start of the topic. As a reinforcement tool, students can engage with the game more consciously, leveraging their acquired knowledge to make more informed decisions during gameplay. Both approaches effectively use the cards to engage students, preserving the fun element and creating a memorable learning experience that integrates play with understanding.

The findings reveal that gamification should be explored further by educators in Singapore, as it can facilitate deeper understanding of abstract concepts that are often difficult to convey through traditional frontal teaching methods.

One effective way to achieve this is through the use of interactive tools, such as card games like GTZ, which engage students in active learning and provide a fun entryway for understanding complex ideas. This approach allows students to actively construct their knowledge, making abstract concepts more accessible and memorable, as it encourages experiential learning rather than passive absorption of information.

To further advance this approach, future research could focus on incorporating intervention-control group studies to measure specific learning outcomes more rigorously. Such studies would provide concrete evidence of the impact on assessment performance, potentially convincing more educators and policymakers of its value.

References

Carrillo-Nieves, D., Clarke-Crespo, E., Cervantes-Avilés, P., Cuevas-Cancino, M., & Vanoye-García, A. Y. (2024). Designing learning experiences on climate change for undergraduate students of different majors. Frontiers in Education, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2024.1284593

Deterding, S. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: defining” gamification”. Proceedings of the 2011 annual conference extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems (pp. 2425-2428).

Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. Pfeiffer.