Young Children’s Voices in Mathematical Problem Solving

Contributed by Dr Ho Siew Yin and Sng Wei Qin Abbie, from NTUC First Campus, for SingTeach Virtual […]

Read More

A CRPP research study is helping Primary 1 teachers know more about their students’ reading abilities.

Students’ success in reading is essential not only for school but also for their daily functioning and lifelong learning in today’s increasingly complex society.

Students’ success in reading is essential not only for school but also for their daily functioning and lifelong learning in today’s increasingly complex society.

The ability to read is a prerequisite for the mastery of knowledge and skills in various academic disciplines such as English, Science and Mathematics. Our daily routines also involve reading to a great extent – may it be deciding which bus to take, reading the restaurant menu or filling out forms.

Currently, little is known about the reading ability of students in Primary 1, let alone the identification of children who are having reading difficulties. As in many other countries, Singaporean children entering their first year of primary school come from a variety of sociolinguistic and socioeconomic backgrounds and have a diverse range of academic experiences. Therefore, it is risky to assume that all children know how to read automatically and fluently once they start formal schooling.

Some children commence first grade without the ability to read or write whereas other children have relatively well-developed reading and writing skills. At the same time, children from families with lower socioeconomic status could be more prone to reading difficulties and lower overall academic achievement as compared to children from families with higher socioeconomic status (Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998).

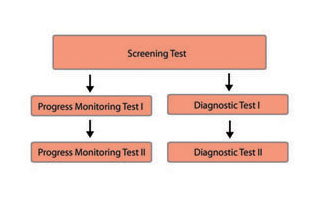

Given these challenges, CRPP’s comprehensive assessment battery is designed in a cascading developmental approach and can be used to assess reading skills in English of both mainstream and at-risk students. It includes the following assessments:

Each test assesses five essential reading skills in primary grades as identified in a report by the National Reading Panel (2000). These skills include the alphabetic principle, phonemic awareness, oral reading fluency, vocabulary and comprehension. Determining the students’ capacity to make use of these skills informs teachers about their strengths and weaknesses and thus provides diagnostic information for appropriate instruction. This is akin to a formative use of assessment data (Carpenter & Paris, 2005).

For mainstream students, reading tasks are organised into three test booklets: the Screening Test, Progress Monitoring I and Progress Monitoring II. The Screening Test involves letter names, letter sounds, rhyming, initial sounds, final sounds, word knowledge and reading comprehension. In the two Progress Monitoring Tests, the tasks included rhyming, initial sounds, medial sounds, final sounds, word knowledge and reading comprehension.

In addition, two in-depth diagnostic tests are administered to at-risk students who have been identified by the Screening Test as those with reading problems. The reading tasks are organised into two test booklets: Diagnostic Reading Test I and Diagnostic Reading Test II. The tasks consist of letter names, letter sounds, rhyming, initial and final sounds, word knowledge, reading comprehension, graded word lists and oral reading.

Currently, the research team continues to work with a number of primary schools in Singapore. At the end of the project, they hope to publish the diagnostic instrument along with a technical manual and market the tests in the South Asia and Southeast Asia regions.

Literacy demands in the information age extend beyond the basic ability to read and write. Young people are now expected to process information and communicate effectively as well. This project helps them do so by ensuring that early intervention and resources are given to those in need.

Luke, O’Brian, and Comber (2001) describe today’s young readers as surfers on an ocean of signs where “postmodern childhood involves the navigation of an endless sea of texts”. So whether or not children can automatically recognise the actual words of these texts, they will be affected by the social and commercial pressures it exerts.

When children exhibit reading problems at an early age, they are at risk of falling behind in terms of both reading and academic achievement. According to Juel (1988), 88% of children who were poor readers in first grade remain poor readers in fourth grade and these problems may persist until they reach secondary school. Extensive research indicates the degree to which underachievement in reading can impede and hinder the full range of academic development (Stanovich, 1980, 1986). This includes the child’s progress in writing, information processing, and communication skills.

As a result, teachers in Singapore are now encouraged to develop finer diagnostic capacities in identifying and tracking students who may require specialised support, an individually tailored intervention or curricular adjustment.

In 2005, the Centre for Research in Pedagogy and Practice (CRPP) began a project to develop a battery of diagnostic reading assessments for Primary 1 pupils in Singapore. These tests were aimed to assist teachers in: assessing their students’ reading and writing skills, determining their specific strengths and weaknesses, identifying those having reading difficulties, and designing instructional plans appropriate for the students’ reading and writing levels.

> Read more about this project here.

References

Carpenter, R. D., & Paris, S. G. (2005). Issues of validity and reliability in early reading assessments. In S. G. Paris & S. A. Stahl (Eds.), Children’s reading comprehension and assessment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Dyslexia Association of Singapore. (2006). Dyslexia in Singapore. Retrieved from https://www.rsi.sg/english/singaporescene/view/20060511153349/1/.html

Juel, C. (1988). Learning to read and write: A longitudinal study of 54 children from first through sixth grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 437-447.

Luke, A., O’Brian, J., & Comber, B. (2001). Making community texts objects of study. In H. Fehring & P. Green (Eds.), Critical literacy. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute on Child and Human Development.

Rust, J. (2000). Singapore Wechsler Objective Reading and Language Dimensions Manual. London: The Psychological Corporation.

Smith, E. V., Jr. (2005). Effect of item redundancy on Rasch item and person estimates.Journal of Applied Measurement, 6, 147-163.

Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Available at: https://books.nap.edu/html/prdyc/

Snow, C. E., Griffin, P., & Burns, M. S. (2005). Knowledge to support the teaching of reading: Preparing teachers for a changing world. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Stanovich, K. (1980). Toward an interactive-compensatory model of individual differences in the development of reading fluency. Reading Research Quarterly, 16, 32-71.

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21, 360–407.

Wright, B. D., & Masters, G. N. (1982). Rating scale anlaysis. Chicago: MESA Press.