Young Children’s Voices in Mathematical Problem Solving

Contributed by Dr Ho Siew Yin and Sng Wei Qin Abbie, from NTUC First Campus, for SingTeach Virtual […]

Read More

Contributed by Wee Kin Guan from Singapore Polytechnic for SingTeach Virtual Staff Lounge

From healthcare services to banking apps, the design of services and products plays an increasingly important role to engage and assist users in the intended role. Former Minister for Education Mr Lawrence Wong emphasized the need of preparing Singapore’s young to be “adaptable, nimble, and innovative problem solvers” (Ang, 2021). The focus of good design is strategic in helping Singapore recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. DesignSingapore Council, the national agency that promotes design, proposed to align design thinking with school curriculums and teach it as a way of thinking (Chin, 2016).

As a discipline, design thinking started to gather traction among academics, entrepreneurs and design communities in the early 2000s (Brown, 2008; MIT Management Sloan School, n.d.; Stanford University, n.d.). In simple terms, design thinking is a human-centered approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success.

At Singapore Polytechnic (SP), we have been teaching design thinking as an innovative process in product and service development for the past few years. In this article, I would like to share my reflection on developing a revamped module for a Polytechnic Foundation Programme (PFP). The module “Fundamentals of Innovation Design” aims to provide the students with basic knowledge in engineering techniques and design thinking.

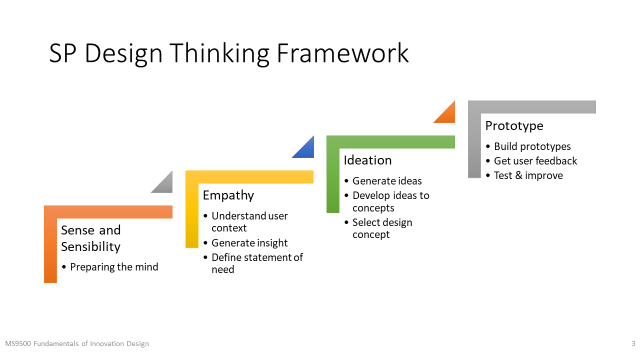

Students spend one semester of instructional time to learn the SP Design Thinking framework, which consists of four fluid and iterative stages: Sense & Sensibility, Empathy, Ideation and Prototype. Each stage has different objectives and intended outcomes as outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. SP Design Thinking Framework and its four stages of development.

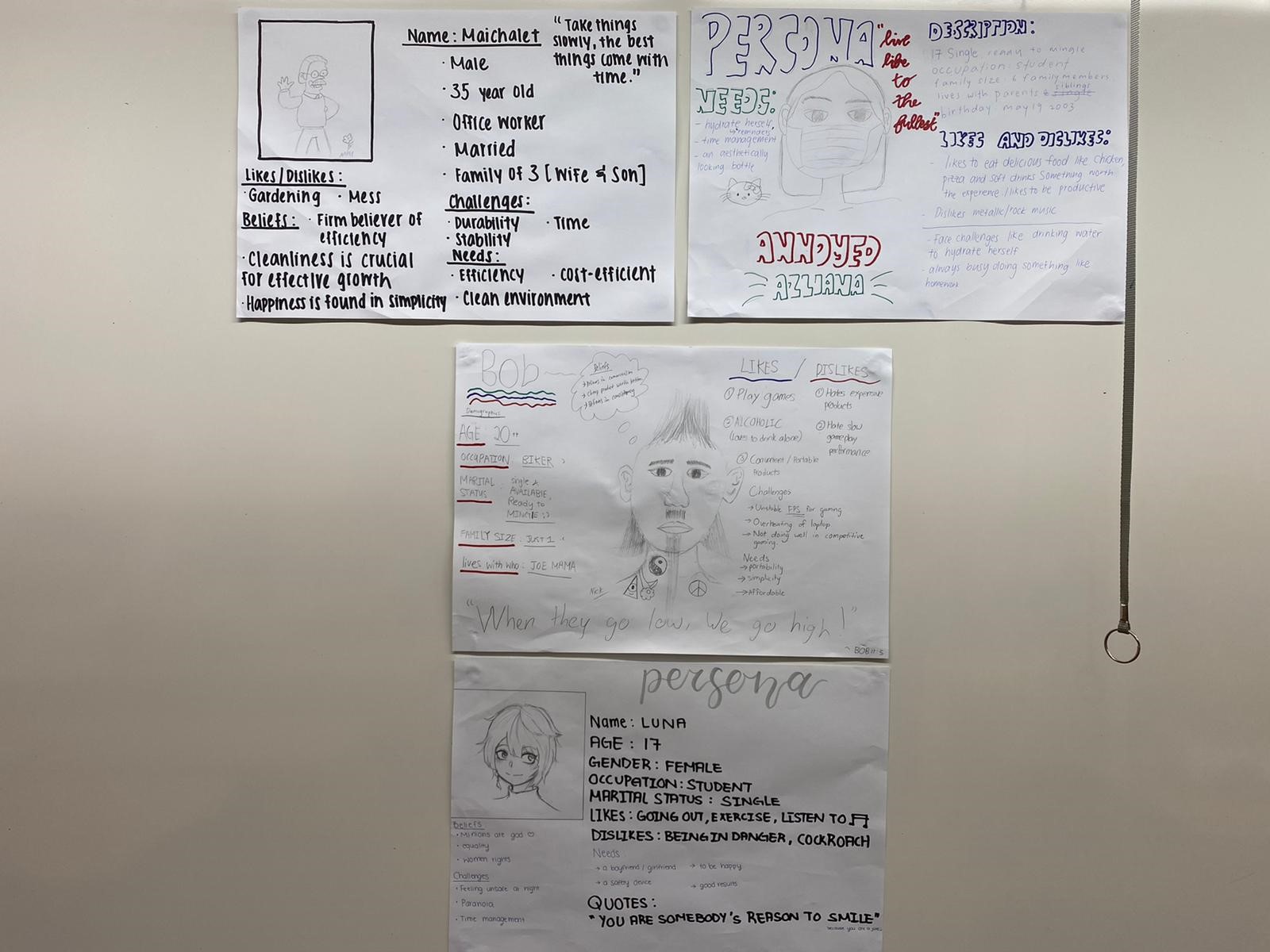

In the first two stages of Sense and Sensibility and Empathy, students conduct interviews with a real local community to identify and uncover insights about the users. Examples include local animal shelters and volunteer centres. They also learnt how to observe users’ activity using a framework to guide the user empathy process. Finally, they will work as a team to brainstorm a problem statement and a persona that encapsulates the user’s needs (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Some sketched personas done by PFP students in the module.

After a short presentation round with the class, the students will discuss ideas and concepts that may address the problem statement of the persona. After the ideation stage, they will subsequently learn the core technologies, such as 3D printing and basic coding with micro-controller, to fabricate a complete prototype that highlights their solution.

After two successful runs of the module, I reflect on some learning points as a developer and an instructor of the module.

Despite the fact that some PFP students might have Design & Technology (D&T) background in secondary school, they could have set their problem statement too wide to be addressed within in a semester, or too narrow to produce any meaningful prototype. By having regular conversations with the student teams, instructors can provide formative feedback to the students over the course of the project. Moreover, not only will the students learn how to solve a problem at cognition level, but also start to monitor their learning progress and readiness (Brown, 2008).

Secondly, the instructors also need to check the quality of the work, especially the interviews transcripts and clustered data points, to help the student teams manage their projects. Based on experiences, the students tended to include too few questions in the first interview with their users. In the second run of the module, we extended the timeline of interview and implemented a feedback session so that students had the opportunity to do the second round of interview with a much complete set of questions.

As a developer of the module, I needed to remain nimble to adapt to unforeseen circumstances should they arise. The most notable example is how we organized field trips for ideation stage in design thinking. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, we used to bring students to local museums such as the Red Dot Design Museum to look at award-winning product designs and to gather ideas amongst their groups. The students would learn and enjoy good design from over 300 design work on exhibition (Red Dot Design Museum Singapore, n.d.).

During the pandemic, we could not organize such trips anymore due to government restrictions, hence we needed to quickly change the plan to home-based learning. We have collated a list of websites related to product design, for example Red Dot Design Award , iF Product Design Award and Singapore Design Awards for students to browse and design their own learning journey. They are encouraged to shortlist interesting products that address their problem statement. At the end of the day, we need to ensure the students achieve the intended learning outcomes regardless of the medium of instruction.

Having developed and taught design thinking for two runs, I have grown to appreciate the discipline. It is not only interdisciplinary by drawing methods from different fields of study, but also immensely relevant to the students. Good designs make a product or service usable, understandable and most importantly, enjoyable.

References

Ang, J. (2021). Use design thinking to help S’pore’s young be ‘innovative problem solvers’, says Lawrence Wong. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/parenting-education/design-is-not-just-a-job-its-a-way-of-thinking-lawrence-wong

Brown, T. (2008). Design thinking. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2008/06/design-thinking

Chin, C. (2016). How is design-thinking reshaping Singapore? GovInsider. https://govinsider.asia/innovation/how-is-design-thinking-reshaping-singapore/

MIT Management Sloan School. (n.d.). Design thinking, explained. Retrieved June 9, 2022, from https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/design-thinking-explained

Red Dot Design Museum Singapore. (n.d.). About Red Dot Design Museum Singapore. Retrieved June 10, 2022, from https://museum.red-dot.sg/pages/about-red-dot-design-museum-singapore

Stanford University. (n.d.). Get started with design thinking. Retrieved June 9, 2022, from https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources/getting-started-with-design-thinking