Young Children’s Voices in Mathematical Problem Solving

Contributed by Dr Ho Siew Yin and Sng Wei Qin Abbie, from NTUC First Campus, for SingTeach Virtual […]

Read More

Contributed by Chan Sau Siong, Choong Tsui Wei, Kendrick Tan, Norazlin Binte Normin, Tan Hup Yew and Angela Teo, from Raffles Girls’ School , for SingTeach Virtual Staff Lounge

From upper left in clockwise direction: Norazlin Binte Normin, Chan Sau Siong, Tan Hup Yew, Angela Teo, Choong Tsui Wei and Kendrick Tan.

Inquiry-based learning (IBL) is generally used in small scale investigations and projects. IBL starts by posing questions, problems or scenarios – rather than simply presenting established facts or portraying a smooth path to knowledge. The teacher takes on the role of a facilitator and students as inquirers. Llewellyn (2010) proposed a seven stages of science IBL at level three. These seven stages are as follows:

The Question

The Procedure

The Results

At this level of IBL, the lesson is student-centred and the teacher serves as a facilitator. Besides designing the lesson, the enactment of suitable teaching actions to facilitate IBL lessons become crucial as it will need to engage students to develop their various scientific skills together with critical thinking skills.

The characteristic of critical thinking is the ability to think logically and abstractly, and to reason theoretically (Paul and Elder, 2007). Socratic questioning is one of the most powerful methods to promote critical thinking through discussion from questioning between students and between students and the teacher (Paul, 1993). A student who trains and disciplines his/her mind to think in Socratic questions to guide the thinking would be able to improve his/her standard of thinking.

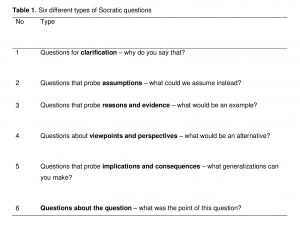

In general, there are six types of Socratic questions as shown in Table 1.

In order to weave in the use of Socratic questions during Science IBL, there are four teaching actions to be enacted to support the discussion.

Firstly, students will focus on a few types of Socratic questions during their discussion and typically, type 1, 2 and 3 (from Table 1) are commonly used in Sciences. These questions are made into cards for students’ quick reference. Table 2 shows how the card would look like.

Secondly, students will be provided with criteria for success to guide their group discussion. These criteria are designed by teachers based on the IBL activities. These criteria provided milestone checks for students as they discuss in their groups.

To initiate the discussion, students are assigned different roles for their discussion. There are three different roles in a group, namely predictor, summarizer and clarifier. Predictor will make claims and lead in the discussion. Summarizer will sum up key ideas at regular intervals and write down important questions and responses. Clarifier will ask questions and seek clarification during the discussion. This role playing action is to help students to collaborate, to help the less ready students and to improve on the depth of their discussion. Students are assigned to the various roles based on their readiness. Those who are the most ready will take on the predictor’s role while those who are the least ready will take on the clarifier’s role.

Lastly, the teacher who serves as a facilitator will walk around to ask Socratic questions to the discussion groups so as to initiate the discussion or to direct students on the right tracts. Teachers will not answer questions directly and help the less ready groups to initiate their discussion.

The use of Socratic questioning has been used in Biology, Chemistry and Physics IBLs in the school’s upper secondary classes. The IBL activities have ranged from exploring a phenomenon (Stage 1 of IBL) to analyzing data and evidence (Stage 5 of IBL). On the whole, both teachers and students have responded positively to the use of Socratic questions in these IBLs based on the feedback gathered from teachers, students and third party observations. Students have been able to achieve the learning outcomes with a deeper level of understanding through the Socratic questions.

This style of questioning is quite innate for the readier students so the structure provided allows for the less ready students to close the gap whilst leveraging on the strengths of the readier students. This is a good form of collaborative learning from one another. The Socratic questions card forces the students to continually seek to find out rather than to sit passively and await answers to fall onto their laps. The use of criteria for success provides a mean for self-directed learning so students can learn and discuss by themselves with less instructions from teachers. Most students enjoy chattering and this discussion provides them an opportunity to do so, thus they are able to have fun whilst learning at the same time.

On the role playing by students, the predictors have been observed to be critical in setting the pace and the discussion on the right track. However, the predictor may be caught in a situation where he/she is not able to handle the questions (due to readiness level, for example) and this can possibly pose problems for the completion of the task given.

Lastly, the IBL task chosen has to be more exploratory where students do not have much prior knowledge. A task where the context is broader or where the solution is more open-ended and complex would allow deeper discussions to take place with Socratic questioning.

References

Llewellyn, D (2010). Differentiated Science Inquiry. SAGE publication.

Paul, R. (1993). Critical thinking: What every person needs to survive in a rapidly changing world. Rohnert Park. CA: Center for Critical Thinking and Moral Critique, Sonoma State University.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2007). Critical thinking: The art of Socratic questioning. Journal of Developmental Education, 31(1), 34–37.