Young Children’s Voices in Mathematical Problem Solving

Contributed by Dr Ho Siew Yin and Sng Wei Qin Abbie, from NTUC First Campus, for SingTeach Virtual […]

Read More

Can English Language teachers make use of social media to teach not just language skills but also important lessons about ethics? Researchers from NIE certainly think so!

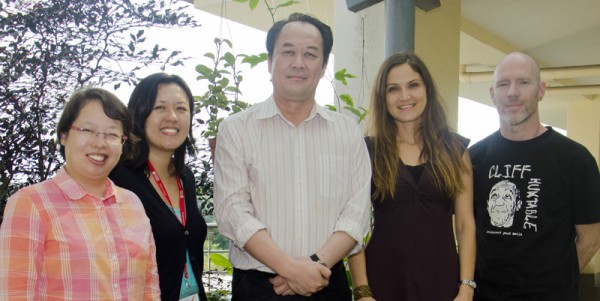

Csilla (second from right) and her team (from left: Suzanne Choo, Katy Kan, Hu Guangwei and Patrick Williams) find that social media can be used to inculcate ethics in learners.

Media literacy is now part of the English Language curriculum in Singapore. But the funny thing is, even though Dr Csilla Weninger and her research team found that visiting social network sites tops students’ media use outside the classroom, teachers refer to social media texts the least in the classroom.

“Both teachers and students need to see the use of social media as an act of literacy,” Csilla notes.

To foster the kind of media literacy that is relevant to students’ daily lives, Csilla and her research team developed a framework with four components: functional, critical, ethical and aesthetic (See box story to find out more about the different components). In particular, the ethical part is something she feels needs more attention in the English classroom.

“From the classroom observations we made, we saw a lot of the functional and critical components being taught,” shares Csilla. “However, the ethical or aesthetic aspects were barely touched on. So we wanted to develop something where the students are required to put themselves in someone else’s shoes.”

In a virtual world where people can hide behind a pseudonym, cases of cyberbullying are rampant among youth.

The ethics component of the media-literacy framework by Csilla’s team asks that students acknowledge and act upon the recognition of the perspective of the other, and take responsibility for their actions.

“If you develop this idea where you have to be able to look at things from a different perspective, then you’re working towards reducing instances of cyberbullying,” Csilla adds.

It may also help students avoid the trap of becoming more and more polarized in their views when they are online. Online discussions sometimes become heated because people care deeply about certain issues, says Csilla.

It may not always be possible for everyone to come to an agreement. The key, she explains, is to “learn to live with and accept differences, which is only possible if you try to step into the shoes of the other”.

Cultivating students who care about others while simultaneously covering the English Language syllabus is definitely possible, says Csilla. While teachers usually focus on specific skills, for this project they decided to focus on a theme.

Csilla’s project team worked closely with English teachers from a school on the theme of SG50 (Singapore 50). They developed an idea that groups of students would each represent a social group in Singapore, such as foreign workers, National Servicemen and families with young children.

Keeping in mind that the English teachers have their own set goals, Csilla’s team used the theme to foster students’ ethical perspective while developing their language skills as required by the syllabus.

For the project, students researched on their respective groups, and read materials such as a blog published by a taxi driver. This helps them understand the concerns and contributions of the group.

To weave in the skill of report writing, they were asked to write a report to their Member of Parliament about a problem their social group is facing. “It is really important that the students understand that the things they are learning have a real connection to their lives outside school,” Csilla emphasizes. “Literacy is a social practice. It’s not something you do in the classroom, examine, and then forget about.”

Csilla notes that in the end, the teachers were able to meet all their set goals. “That’s the wonderful thing – it’s possible to meet all those requirements and everybody’s learning objectives, but have it done in a way that’s more meaningful than just a unit on report writing!” she enthuses.

Moreover, she found out that it was not just the two teachers she worked with that used the materials—all the other teachers teaching the same level joined in because they thought it was interesting for their students.

Csilla suggests that teachers keep themselves updated about social-media happenings and talk about them in the classroom. “Things like the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge – have discussions about them, ask students for their reactions, and how they participate in social media,” she says.

Csilla suggests that teachers keep themselves updated about social-media happenings and talk about them in the classroom. “Things like the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge – have discussions about them, ask students for their reactions, and how they participate in social media,” she says.

However, she cautions that while it is important to establish relevance and connections, teachers should be careful not to intrude students’ privacy to a life outside school.

“It’s a delicate balance,” she notes. “It’s important to prepare students for what they encounter online and empower them to be active media users. But it’s also critical that we leave them the social space where they can enact agency and talk about issues they don’t want their teachers to talk about.”

Striking that balance is not easy, but Csilla believes that it is especially important for a holistic education.

“Our students are human beings with emotions, and they have agency, desires and plans. As educators, we should pay attention to those other parts of our students as well, to develop them as a whole person. And this is where media literacy is important in this current age.”