Young Children’s Voices in Mathematical Problem Solving

Contributed by Dr Ho Siew Yin and Sng Wei Qin Abbie, from NTUC First Campus, for SingTeach Virtual […]

Read More

The Centre for Research in Pedagogy and Practice (CRPP) has undertaken a large-scale language survey. The survey involves 1,000 Primary 4 students from the three main ethnic groups in Singapore. It is hoped that these children’s language patterns and attitudes can be documented.

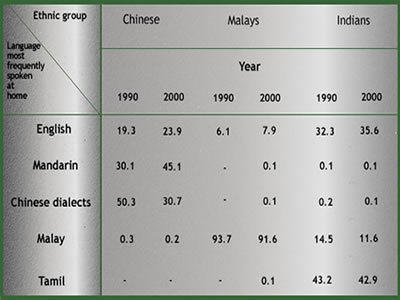

The census is a document that presents the broadest possible view of language use in a nation. In terms of language, the Singapore Census asks what the language most frequently spoken at home is. On the basis of this question, the following decadal trend can be observed:

Table 1. Language trends in Singapore. (Source: Census of Population 2000, p. ix)

It is clear from these statistics that English has increased somewhat as a language most frequently spoken at home, especially for the Chinese community, and that there are substantial gains for Mandarin and losses for Chinese dialects. The number of Indian homes where English is the household language has not increased except by 3.3% though this number was high throughout the last decade compared to the Chinese and Malay communities.

Viniti Vaish, Norhaida Aman and Wendy Bokhorst-Heng

However, this is merely the surface of the language situation in Singapore. If Singaporeans were asked what their most frequently spoken language was, they are likely to answer “it depends”. Xu and Li (2003) commented that “What is not reflected in the census report is the indecisiveness (uncertainty) of many Singaporeans when asked about what is the language they use most frequently in a specific type of situation, e.g. at home; neither does the report reflect the practice of code-switching among the young people”. The Sociolinguistic Survey of Singapore tries to address this shortcoming with the following in-depth research question:

Who speaks/writes what language to whom in what context with what level of fluency with what communicative ends and with what attitude?

A few similar studies have been done in Singapore (Goh, 2001; Xu, Chew, & Chen, 1998). Goh’s (2001) findings were that though the younger cohort of Chinese language teachers that had been trained under the current bilingual education system rated their Mandarin as being better than their English, that was not the case in reality. In actual fact, “there is a sharp disparity between their actual proficiency level and their self perceived language competence” (p. 238). The latter, a much larger study of 4000 Chinese in Singapore, found that acceptance and use of English was less than that of Mandarin. Though this is probably the largest sociolinguistic survey done recently in Singapore, it only surveyed the Chinese community.

The following comment by the authors is one of the inspirations for our study: “A pan-community survey reaching all sectors of the population was never attempted by the academics” (Xu, Chew, & Chen, 1998). The Sociolinguistic Survey of Singapore is such a pan-community survey.

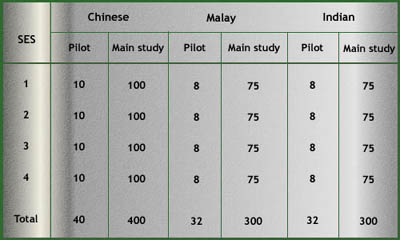

Our study differs in terms of the age of its cohort, the depth of the survey questions, and the theorizing of the instrument and data. The following table summarizes our research design:

Table 2. Ethnicity and socio-economic status of participants.

Our sample is stratified by race and socioeconomic status (SES). Due to anticipated difficulties in getting enough families to fill each cell, we have decided not to include the ethnic category “Others” in our study. The four SES groups are based on the following census categories: high, upper middle, lower middle, and low.

Nearly 15 schools from diverse neighbourhoods have volunteered to participate in this study and we hope to involve many more. However, the administration of the survey will take place in the home.

Though both Goh (2001) and Xu, Chew, & Chen (1998) used only self reports without any stimulus, The Sociolinguistic Survey of Singapore uses scenarios in the form of audio recordings that will be played to the children on the basis of which they will answer questions on language attitudes and ideology. These scenarios are in English, Malay, Mandarin, Singlish, and Tamil, and will be administered in keeping with the ethnicity and linguistic background of the children by bilingual researchers who are insiders of the different linguistic/ethnic communities.

We hypothesize that the languages and registers that children bring to the classroom might have an impact on their educational achievement. For instance, a child who speaks mainly Malay and Singlish at home might deal with the curriculum differently compared to another child who speaks only Standard English at home. One of our concerns is to explore whether this differential linguistic capital that children bring to school leads to differential educational outcomes.

We hope that this study would provide constructive data that can inform Singapore’s bilingual education policy and language teaching.

Data collection is divided into two stages which will run without a substantial intervening gap.

Stage 1: Questionnaire

We will survey 1,000 students from the primary 4 cohort. The rationale for this is to capture the patterns of language use and attitudes of children before they reach secondary school so as to make suggestions founded on this baseline data for improving language teaching at the secondary level. The survey instrument is divided into the following “social fields”: family and friends, religion, school, public space, and media. We also have items on language and literacy proficiency.

The questionnaire is administered in a face to face interview by a bilingual researcher from the same ethnic group and language background as the respondent. At this meeting (or soon after), an observation guide which documents the nature of books and magazines in the home and other artifacts of interest to this project would be filled out.

Stage 2: Follow-up studies

This survey will lead to follow-up studies with a smaller cohort of students from the initial 1,000. These follow up studies, which are currently being pre-piloted, will consist of 24 cases across the three ethnic groups and the four socioeconomic strata.

For each ethnic group, we will follow up with two respondents, a boy and a girl culled from those interviewed at the questionnaire stage who have agreed to participate in a follow-up study. We aim to get in-depth documentation of the children?s patterns of language use across the five social fields.

The purpose of the follow-up studies is to verify the findings of the questionnaire and provide documentation of code-switching patterns in the home. These studies involve a series of visits. In the first visit, the researcher shows the social fields, simplified as topics, to the parents and requests for the times that she can observe the child in the relevant situations. After this initial visit all subsequent visits are tape recorded and, if allowed, video recorded. During these visits, the researcher is a methodological omnivore and chooses her strategy from the following options depending on the cultural context:

This project, which is currently in the pre-pilot stage, extends till August 2007. At the end of the data collection we should have 1,000 completed questionnaires and 24 cases studies.

For more information on The Sociolinguistic Survey of Singapore, click here.

References

Leow, B. G. (2001). Census of population 2000: Education, language and religion. Singapore: Department of Statistics.

Xu, D., Chew, C. H., & Chen S. (1998). Language use and language attitudes in the Singapore Chinese community. In S. Gopinathan, A. Pakir, W.K. Ho & V. Saravanan (Eds.), Language, society and education in Singapore (pp. 133-155). Singapore: Times Academic Press.

Xu, D. & Li, W. (2003). Managing Multilingualism in Singapore. In W. Li, J.D. Marc & A. Housen (Eds), Opportunities and challenges of bilingualism (pp. 275-295). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.