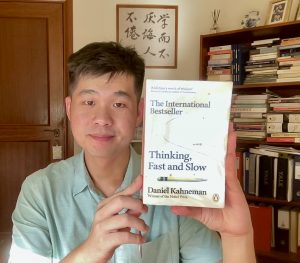

A Teacher’s Toolkit from the Cognitive Psychology of “Thinking Fast and Slow”

Contributed by Seow Yongzhi , from Broadrick Secondary School, for SingTeach Virtual Staff Lounge

Dan Kahneman’s brilliant book, Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011), is a powerful primer for all of cognitive psychology. Economist Steven Levitt christened it “a lifetime’s worth of wisdom”. In the book, Kahneman describes a model of human cognition in which humans operate by two thinking systems: System 1, which is fast thinking that operates based on biases and heuristics; and System 2, which is slow thinking that operates based on deliberation, logic, and use of evidence. We make many decisions under time pressure using System 1, and unseen cognitive biases may lead to errors in judgement.

I read the book for personal growth amidst the pandemic, but nevertheless found many gems of insight that could be extended into my professional pedagogical practices. In this article, I summarize five key findings on cognitive psychology from Kahneman’s book, and identify applications in our professional processes.

1. Regression to the Mean

A key statistical principle is that people tend to perform close to (their) average. If someone does exceptionally well on a test, they are likely to do “worse” for the next test; and if someone has done very poorly, the “only way to go is up”. Flight instructors felt that punishment was an effective pedagogical tool, because poorly performing cadets improved after being punished. However, Kahneman demonstrated that “poor performance was typically followed by improvement and good performance by deterioration, without any help from either praise or punishment.” In other words, the flight cadets would likely have “improved” in their next performance regardless of the intervention; however, praise would have had better effects on the cadet’s morale than punishment.

Teacher’s takeaways

- If you reprimand someone and they improve, and if you praise someone and the performance dips – this is normal: it is regression to the mean.

- As teachers, we can consciously resist the perverse incentives to punish more and praise less. As a general rule of thumb: praise is good, punishment is bad.

2. Building Competencies

Expertise is a set of interlinked skills. There are two requirements for building skills: “an environment that is sufficiently regular to be predictable [and] an opportunity to learn these regularities through prolonged practice”. However, some domains (such as gambling) do not allow for the development of skills, because the environment is not regular. Our teaching subjects and many CCAs in our schools do meet such requirements, and are ideal pastures for the building and development of expertise.

Teacher’s takeaways

- Developing a skill requires regular practice. As a Social Studies teacher, I teach source-based skills to my students such as making inferences, comparing and contrasting sources, and evaluating the reliability of sources. Following the first lesson with teacher modelling, I make sure to include practice sources and questions for students to rehearse the new skill.

- Practice must be matched with consistent high-quality feedback. Kahneman’s research affirms that our routine marking of student practices and assignments, is a powerful and important tool in building our students’ thinking and writing skills.

3. “Inside” and “Outside” Views

“Insiders” tend to have an irrationally optimistic view of their team’s effectiveness and progress, and may ignore data or findings to the contrary. The example used by Kahneman, intriguingly enough, involves a project to write a psychology textbook for Israel’s Ministry of Education. Kahneman’s takeaway was that his team was plagued by “irrational perseverance: … we gave up rationality rather than give up the enterprise.” In other words, people “inside” a project, with a stake in their success, failed to be objective in their evaluation of their team’s effectiveness.

Teacher’s takeaways

- We tend to think of the best case, not the probable case, when planning events and projects. Hence, we should always refer to past data for reliable estimations when planning workflows and timelines.

- For example, I organised a cohort learning journey to the National Museum this year. The slots opened in October 2022. Even though I opened the booking system armed with our school’s preferred dates and timeslots the very moment the system went live, I only managed to snag half of what we wanted. If we had dithered, perhaps we would miss out on all available slots and have to adjust the school calendar. Given this data, I learned to engage all external vendors at the earliest opportunity.

- Get outside opinions and evaluate them rationally. If a project is unviable, ignore the sunk costs and dump it. Similarly, if an approach to teaching is not working, consider trying new methods rather than “persevering irrationally”. The relevant data comes naturally to the teacher, when we mark our students’ practices and worksheet.

4. Framing Effects

The way that we ask (or “frame”) a question will lead to different answers. For example, countries ask drivers if they are willing to donate their organs in the event they are involved in a fatal traffic accident. This is an important decision that could save many other lives. The difference in drivers’ willingness to donate lies in the way the question is asked: where drivers need to “opt out” of donation, there is an extremely high donation rate; but where drivers need to “opt in” to offer donation, there is a very low donation rate. In general, people are biased towards cognitive ease: people prefer to go with a default option, rather than make the effort to “opt in” or “opt out” of anything.

Teacher’s takeaways

- When you seek genuine interest for an event with limited slots (such as a school competition or performance), you can invite volunteers amongst your students. These volunteers, in paying the cognitive cost of consciously stepping forward, will be more invested in your event.

- When you want to nudge higher student participation in an activity that has high capacity or benefits from having more people involved, make sure to use automatic enrolment and an “opt out” option instead of asking for volunteers.

5. Peak-End Shaping of Memory

People remember life events and episodes in terms of their best (and worst) moments, as well as how the event or episode ended. In fact, when evaluating one’s entire life, Kahneman found that “peaks and ends matter but duration does not”. This intuitive judgement plays an important role in deciding whether to repeat the event or episode.

Teacher’s takeaways

- After students’ significant experiences (e.g. field trip, CCA performance), make sure to celebrate and recognize the students’ achievement. The end of the experience matters greatly in the students’ memory.

- Create memorable moments for students on a school trip; it adds to the peaks that stay with our students for the rest of their lives. For example, we led our Co-Curricular Activity (CCA) students to the Singapore Youth Festival (SYF) showcase this year. Our school team made sure to take pictures with family and friends who came to support the team, in order to commemorate the milestone in their CCA journey. We made sure to celebrate everyone’s efforts and the strenuous journey towards SYF, and the competition ended on a brilliant high.

Reference

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.