Customizing Learning

School-based curriculum innovation is no easy task. We talk to a team of Science teachers who has collectively designed a customized curriculum for their Normal (Technical) students.

There is never a boring day at Crest Secondary School, says Mr Adrian Tay, Head of Department of Math and Science.

Set up by MOE, Crest Secondary is the first school in Singapore to specialize in educating Normal (Technical) (NT) students. To date, they have around 400 students. By 2016, that number will double. “You can imagine that it is an exciting place to work in!” says Adrian.

The school has a clear purpose and mission: to transform students into confident individuals who are empowered to realize their dreams.

“We know our students have certain learning needs and interests,” says Adrian, “so our mission is to provide a caring and creative learning environment that customizes authentic learning experiences, and equips them for academic progression and employment.”

To fulfil that mission, the Science team designed their curriculum based on four theoretical influences.

Fixed versus Growth Mind-set

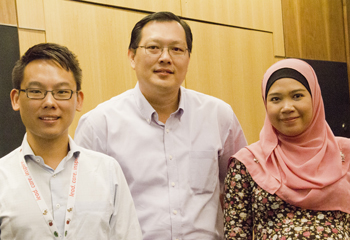

The team of Science teachers consists of (from left) Adrian Tay, Ong Kwang Wei and Noor Khairin.

Your intelligence is fluid. It can be developed through effort and learning.

Which statement do you believe in? According to Stanford University psychologist Carol Dweck, if you had chosen the first one, you probably have a fixed mind-set. If you went with the second, you have a growth mind-set. And what you believe in will drive your behaviour.

For example, people with different mind-sets will aim for different goals.

“Those with a fixed mind-set have performance as their goal. They go for grades,” explains Adrian. “However, for those with a growth mind-set, the goal is learning.”

The way they react to stress and failure will differ as well. “Sometimes, a student with a fixed mind-set may not want to try a second time after failing once,” Adrian says.

“To them, it would seem pointless, since they see failure as a measurement of their intelligence or ability, which they believe is an entity that cannot change. Refusing to put in the effort to try harder can also be a face-saving tactic.”

Those with a growth mind-set will focus on learning from experience and becoming better. This kind of mind-set is what teachers at Crest want their students to have. “We don’t want our students to be defined by their past results or failures, or what they think they’re not good at,” explains Adrian.

The State of Flow

If you give your students an easy problem, they will soon become bored. But get them to solve something too challenging, and they may turn anxious.

There is a “delicate, tricky balance” between students’ skills and the given challenges that teachers have to maintain in the classroom, says Adrian. If they get it right, students will become engaged, and even enter a state of flow.

The psychologist Mihaly Csikzentmihalyi coined the term to describe a state where people enjoy and are fully immersed in an activity. Distractions are typically ignored and time seems to stand still.

Zone of Proximal Development

Developmental psychologist Lev Vygotsky developed the concept of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) to describe the zone between what a student can do independently and what he or she can achieve with help.

“How do we help students get from where they currently are to the next level?” Adrian asks. It is through scaffolding, or guidance from a more knowledgeable other, such as a teacher.

Adrian sees a convergence of a growth mind-set, the state of flow and ZPD, as they all assume the possibility of growth, facilitated by teachers who strike the right balance between challenge and skills through thoughtful curriculum design. These teachers provide the necessary scaffolding to help their students achieve success.

Understanding by Design

Understanding by Design is a framework for educational planning developed by two education experts Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe. The first step requires teachers to identify the desired results. Then, they need to determine what would be acceptable evidence to answer the question: “How will we know if students have achieved the desired results?” Finally, teachers plan the learning experiences and instruction.

“In a nutshell, start with the end in mind,” Adrian says. And from there, work backwards. Working on this process is a team effort, and all the teachers take ownership over curriculum design.

Main Features of Assessment Tasks

Influenced by these theories, Adrian and his team designed the Secondary 1 Science curriculum for their students. Projects and practical assessments make up 40% of their final Science grade

The assessment tasks the teachers came up with share three common features.

1. Performance Tasks

To assess student understanding, and to give their students learning experiences that are both hands-on and “minds-on”, Adrian and his team created performance tasks. which they hope would create the need to learn, and hence motivate learning.

“According to Wiggins and McTighe, understanding is revealed in performance. Compared to pen-and paper tests, a performance task is a more complex, authentic and unstructured form of assessment that yields tangible products and performances. Ideally, they should be realistically contextualized,” Adrian explains (Find out about their performance tasks in the box story below).

To ensure a balance between challenge and skills, the difficulty of the tasks had to be carefully calibrated. Clear scaffolding was also crucial.

2. Scaffolding

Scaffolding can take many forms, including benchmark lessons, which Krajcik et. al. (1999) described as lessons in which students do not learn concepts for the sake of learning them, but instead to help them understand and find solutions to the driving question of a project. Teachers need to help students see how these lessons connect to their project.

A template that provides structure for students can be very useful, as are examples of good work.

Adrian’s team also works with other departments so that the knowledge and skills learned in different subjects could be used in tandem for a single project (e.g., ICT skills to do online searches and create Google presentations).

3. Showcase

To celebrate and affirm students’ successes, platforms are created to showcase excellent work.

In the case of Project Weightlifter, the team that built the best contraption (which involved a combination of a wheel and axle system and a compound pulley system) was invited to present and demonstrate their contraption to their peers during assembly.

As for the nutrition project, the teachers selected the best teams to present their set lunch menus to the school. Students and teachers then voted for their favourite menus. The teams with the most votes got to work with teachers from the school’s Retail and Hospitality Department to prepare the meal for their school leaders.

Every Student Matters

“At Crest, we believe that every student matters. They are all valuable and important to us. And they all can learn.” Because of such beliefs, Adrian and his colleagues are working hard to align their curriculum to their students’ needs.

Ultimately, they hope to see their students graduate and live out the school motto: “Empowered to Realize My Dreams”.

Reference

Krajcik, J., Czerniak, C., & Berger, C. (1999). Teaching children science: A project-based approach. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill College.