Collaborating in the Chinese Classroom

Pair up a centuries-old language like Chinese with games, and what you get is a classroom of excited pupils working hard (and smart) with their classmates to form the most complex Chinese characters possible.

Learning to recognize Chinese characters can be a challenge for some pupils. Can we find a way to make it more fun and less daunting for them? NIE researchers put their heads together for an answer, and came up with a clever mobile app called Chinese-PP.

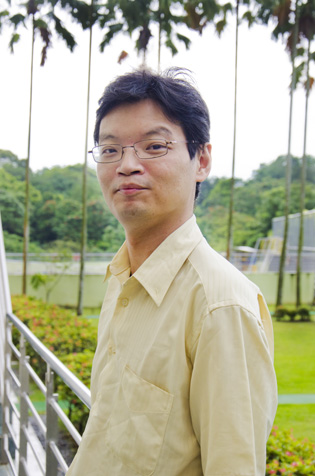

But playing in the classroom isn’t just fun and games. “We want to go beyond playing games,” says Dr Wong Lung Hsiang, who headed the research team. “We designed a curriculum to teach pupils orthographic awareness, which is the understanding of the structure of Chinese components.”

Room to Learn and Interact

What sets this game apart from others is that the pupils didn’t play in fixed groups. They chose which group they wanted to join by matching their component with others.

What sets this game apart from others is that the pupils didn’t play in fixed groups. They chose which group they wanted to join by matching their component with others.

This idea of “flexible grouping”, as Lung Hsiang calls it, allows the pupils to develop both content mastery and other competencies, such as agency, negotiation, collaboration and critical thinking.

Because pupils worked in flexible groups, they were not just learning Chinese characters, but also learning how to interact and negotiate with their classmates as they moved around the classroom.

Getting learners to “promote” their components to others to form higher scoring characters also ensures that they thoroughly understand their components.

At first sight, this “chaotic” classroom seems a little hard for the teacher to manage.

“But if the students are very engaged in these games, then it’s a different story. The students loved playing these games. They were very engaged and quite focused,” says Lung Hsiang.

Flexible Learning

The game offered two game group modes: single and multiple. Single-group mode meant pupils could join only one group. In the other mode, they could join multiple groups simultaneously. Regardless of the mode, which group(s) they wanted to join was entirely up to them.

As in any game, pupils wanted to do their best by trying different strategies to achieve the highest scores possible. They formed the most complex word they could in the single-group mode, or joined as many groups as they could in the multiple-group mode.

“They figured out all different types of strategies by themselves,” says Lung Hsiang. “We didn’t need to teach them these kinds of higher order thinking skills.”

The game made it easier for them by giving them the option of a trial run, where they could form characters by themselves before approaching their classmates.

Lung Hsiang recalled that sometimes, there were pupils who found themselves without groups. When they asked peers who were already in groups for assistance, help was usually given willingly. The peers gave advice about what characters they should form, or even broke away from their current group to form a new character with the pupils in need.

Learning by Making Errors

Through Chinese-PP, pupils learned Chinese in a manner that is vastly different from the traditional approach.

Instead of memorization, this game-based learning curriculum uses the trial-and-error method – something you wouldn’t think would be used for learning Chinese.

“Trial and error is a good way to learn,” says Lung Hsiang. “Even if you come up with the wrong character but put the component at the right space, you still get a score. So, it’s not a clear-cut ‘yes’ or ‘no’.”

Pupils had to try and understand why they had failed, which led them to the right answers. “Don’t try to teach everything,” Lung Hsiang advises teachers. “Give them some space to grow by themselves. If not, it’s just direct transmission and they won’t necessarily internalize.”

When they compared the experimental class to the control class, the research team found the former clearly had a higher orthographical awareness.

Through this higher awareness, Lung Hsiang hopes these pupils can make educated guesses if they were to encounter unfamiliar Chinese characters in the future.

“You can make some clever guesses. Like this component (氵), you’ll know it’s something to do with water or a liquid.”

To him, Chinese isn’t just about memorizing characters as a whole or strokes sequences – understanding the components matters just as much.

With games, even a centuries-old language such as Chinese can be learned in a new fashion. More importantly, it’s fun and engaging for pupils, and they become more flexible and collaborative learners along the way too.

A lesson was made up of three activities: a pre-task, the game and a post-task.

A lesson was made up of three activities: a pre-task, the game and a post-task.