Linking Learning to Life

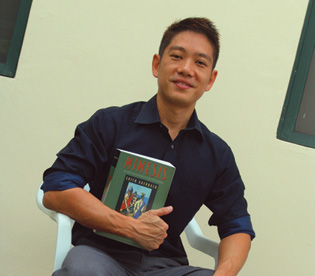

Warren Mark Liew is Assistant Professor with NIE’s English Language and Literature department. His early ambition was to be a professor of English Literature specializing in English Renaissance poetry. All that changed when, he says, “I started teaching and experiencing the real challenges of classroom teaching.”

It all started with a love for literature – and a desire to make the subject come alive for his students. Formerly a secondary school teacher, and now a teacher educator at NIE, his teaching philosophy is to make learning real and relevant, both for himself and for his students.

“Like any subject in the school curriculum, the study of teaching should be made real,” says Warren. “There’s a need to join theory and practice; not see them as dichotomous.”

Q: Is there an area of education that you are especially interested in?

A: I am interested in how teachers can dissolve the barriers between the school and the larger world outside the classroom.

This goes back to the educational tenets of thinkers like John Dewey, who believed that life in school should not just be a reflection of life in society, but also assimilate the elements of that larger reality. As a microcosm of the real world, the school should prepare students for the demands and responsibilities of real-world citizenship.

Q: Why are you so passionate about this?

A: It grew out of an ongoing conviction that I wasn’t going to learn anything in school if I couldn’t see how it affected me in real life.

The subjects that captivated me most were those that made me think and feel, that made the vital connection between my intellectual and emotional life. So Literature was my favourite subject. It made me think and feel deeply about the lived realities of the human condition.

Now, I want to do the same for my English language and literature students what my best teachers did for me. I want students to see the significance of what they are studying in relation to a world beyond that of assignments, examinations and grades.

Q: How did you come to be interested in education research?

A: I had the good fortune of being in an independent school that valued research pursued by teachers as part of an ongoing professional development programme.

One of the requirements of the programme was an independent school-based research project, where teachers could analyse and evaluate elements of school curriculum, or conduct action research on their own classroom teaching. Teachers were also encouraged to present their research findings at local conferences.

Over the years, I became excited with the possibilities and implications of teacher-led research, particularly the idea that teachers themselves can be stewards of their own professional learning, and sponsors of school-wide curricular reform.

Q: How has your teaching experience affected the way you view research?

– Warren Mark Liew, English Language and Literature Academic Group

A: As a school teacher, I was still very interested in research and scholarship. I didn’t want to give up that part of learning, and tried to read books and journal articles whenever I could. Teaching is such a busy job that there is hardly any quality time to do this, so it is good to have a school culture that actually encourages that.

My teaching experience taught me to value the role of research in enhancing teachers’ professionalism. I think teachers need to have that kind of intellectual stimulation, the same kind they provide for their students.

If all they do is just teach to the test, or win performance awards and plaudits, then they become no more than passive administrators, rather than thinking professionals like doctors and lawyers.

Q: What do you think research can bring to the classroom?

A: This has to do with the so-called theory-practice nexus. To what extent can theory truly benefit practice? How does practice relate to theory?

The traditional notion is that theory is the knowledge that has been scientifically gathered by researchers and put out there in scholarly journals and books for practitioners to apply. According to this view, good teaching practice ought to be a reflection of good theory.

The more progressive position – and the one I subscribe to – argues that both theory and practice are mutually informing. Theory is knowledge that has been systematically codified and disseminated, but that knowledge alone is not sufficient to carry on to good practice. Theory is always in the process of evolving and changing, and practitioners have a leading role in advancing this process.

Q: What does this mean in practical terms?

A: At the end of the day, practice has the ultimate say. Real-world practice can always refine and redefine theory. And I think academics can learn a lot from school teachers.

Going into the classroom is a reality check. It’s hard to fully comprehend the complexities and challenges of teaching otherwise. It’s not so easy to be a theoretician or an academic, to write papers and read, but it’s even more difficult to practise what you preach.

It would be ideal to have researchers go back to the classroom every now and then and do the work of teachers, and for teachers to exchange places with academics and do their kind of work in return.

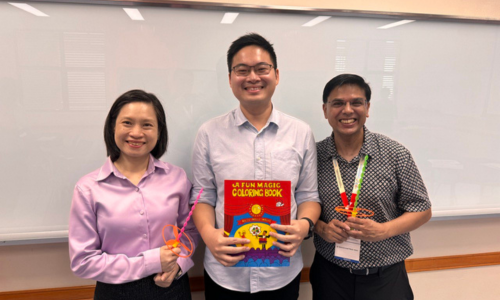

Q: How can teachers engage with research in education?

A: I think it has to begin with a research culture in schools that prizes teachers’ active engagement with scholarship, and encourages them to adopt a stance of active and critical inquiry in their everyday work.

– Warren on the benefits of research

Research shows that the way to make teachers more professional is to have a learning programme that is sustained and ongoing, that makes teachers constantly reflect on their work in light of new knowledge. Professional development is about empowering teachers to be knowledge producers and not just knowledge consumers.

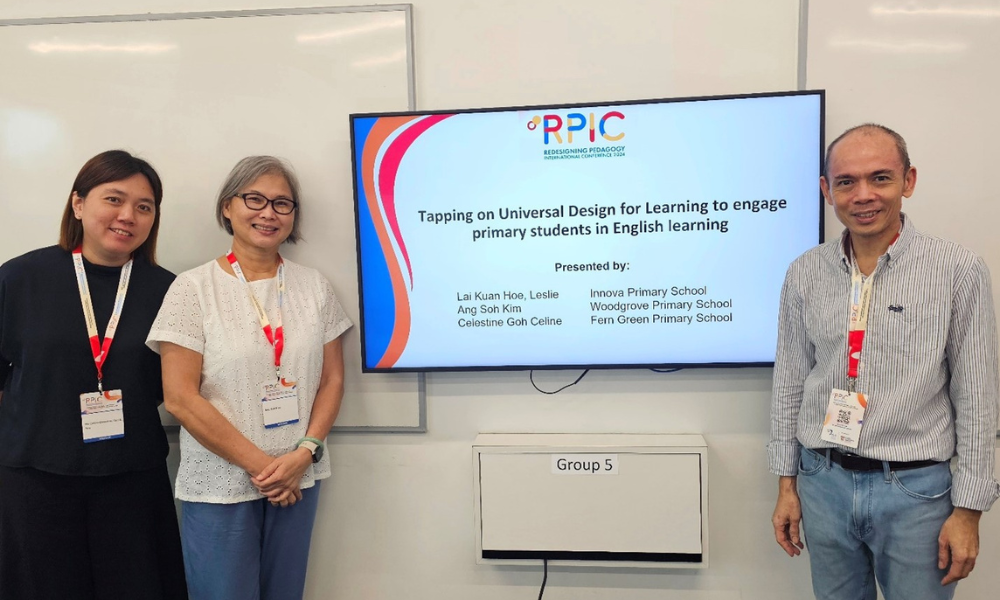

There ought to be a practicum element even in one-shot in-service workshops and seminars. Teachers shouldn’t just go to conferences to listen and enjoy the buffet lunches.

They should go to these conferences to present their classroom research. It helps when they have audiences who are willing to critique their work and make them accountable for their research findings.

Q: What do teachers stand to gain from this?

A: I understand that not many teachers have an appetite for research, partly because of the misconception that theory is esoteric and academic, whereas practice is relevant and real.

Teachers should be excited about research. For those really interested in research, it will be a transforming experience. Research can stand to benefit teachers if teachers think of themselves as researchers in their own right.