What Students Want to Achieve

Competitive. Grade-conscious. Materialistic. The stereotype of the students in Singapore is one that seems to be mainly driven by economics and success. However, a recent CRPP research study tells us that our students’ goals are not as simple as they seem.

Dennis McInerney (centre) is a Professor at the Centre for Research in Pedagogy and Practice at the National Institute of Education. His research team includes (from L-R) Research Fellow Arief Liem and Research Assistants Adelaine Manzano, Lee Jie Qi and Yasmin Ortiga.

Preliminary data from a CRPP research study shows that while high grades and rewards are still important reasons why students want to do well in school, they’re not necessarily at the top of their lists.

On the contrary, survey results indicate that students are likely to study hard because they want to improve their performance, are interested in what they’re learning or want to help friends who may be having a hard time in class.

Described by Principal Investigator Dennis McInerney as a “quick hit of information”, this one-year study aims to give teachers a general idea of what drives their students to learn and achieve in school.

“As far as we are aware, no one has done an extensive study on how Singaporean students conceptualise their future and where schools fit into their futures,” says Prof McInerney. “We want to know if students see a connection between their future goals and what they do day-to-day in their classrooms.”

And to find out exactly what motivates a student, the research team surveyed a total of 5,773 students, talked to 50 parents and teachers and conducted 80 student interviews in 13 neighbourhood schools across Singapore.

While the team has focused on areas that have been known to influence student motivation, understanding student goals is a key part of their research.

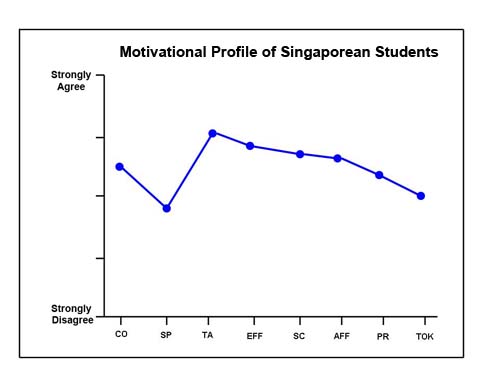

What Students Want Now

Although the team is still at the preliminary stage of their analysis, what they have found out is already challenging common beliefs about how students in Singapore are motivated in school.

For one, “doing better than my classmates” was not strongly endorsed as a reason why students want to study harder. The usual suspects such as rewards and praise also did not rank as high and “leading or being in charge of a group” received the lowest score among the students.

While many students in Singapore may seem obsessed about their grades, they’re not necessarily driven to be the best in the class. In fact, the act of comparing grades with their peers is not always a matter of competition but an affective way of monitoring one’s own progress.

According to students interviewed, scoring higher than their peers made them feel happy – not because they beat the competition but because they felt like they had improved their performance.

“I think we need to look beyond what we can see from the obvious,” says Arief Liem, the project’s Research Fellow. “Yes, students’ immediate goal may be good grades but perhaps they want good grades because they want to achieve certain future goals. Grades may be the only tangible thing we observe motivating them but beyond that, there are other psychological factors.”

“I remember interviewing a student who said she really wanted to win an award at school because it came with money,” recalls Yasmin Ortiga, a member of the research team. “At first I thought it was all about the prize but it turned out that she wanted to win the money because it made her feel proud to give it to her parents and contribute something to the household.”

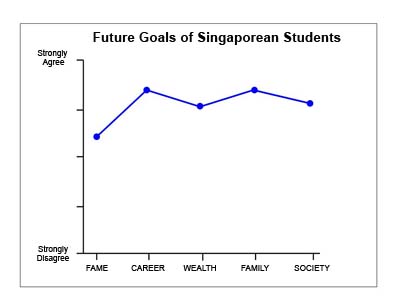

What They Want Later On

Aside from the current reasons why students want to achieve academically, the research team also explored more distant goals – or aspirations that students set themselves for the future. Both are important things to consider when encouraging students to plan their lives.

“It’s a little dance between valuing what you are doing now and also seeing how it works to secure one’s future,” explains Prof McInerney. “If students value a particular future but are not seeing what they’re doing now at school as preparing them for that future, then school becomes purposeless and perhaps meaningless for them.”

“The stronger the connection between students’ current goals for achieving at school and their perceptions of school’s importance for achieving a future, the more motivated they become. And teachers are very important to help establish that connection,” he adds.

Based on survey results, students indicated that getting a good job and supporting one’s future family were definitely top priorities. Interestingly, future goals concerning wealth received a slightly lower score, and goals which had to do with becoming an important or famous person received the lowest score.

While having such goals may seem like something that comes naturally, the research team believes that teachers should be more conscious of encouraging their students to plan for the future.

Adelaine Manzano, a member of the research team, agrees that not having any future goals can affect how students regard the value of school. “There are kids we talked to who do not express that they understand the value of schooling,” she says. “They think that they need to wake up every day because they have to go to school and that’s practically it.”

And while some may doubt teenagers’ ability to come up with concrete plans for the future, Prof McInerney believes that it’s not a matter of forcing them to make a final decision. “I don’t believe that kids of about 15 or 16 are not able to articulate a future,” he emphasises. “It may not be clearly a specific career but it can be a future that says, ‘I am going to progress, learn and become the best I can.'”

“I think what’s important for kids at this age is to set them thinking about their futures and school’s connection to that future,” adds Lee Jie Qi, another member of the team.

What’s Next

As the research team continues to analyse their data, they hope to draw more connections between goals, other psychological factors such as values, self-concept, learning strategies, and how students see the value of school.

Hopefully, this will eventually lead to answering the important question of how all this fits into helping students learn better.

“Having goals is one thing but how do students actually go through the steps to achieve those goals?” says Prof McInerney. “We are not just looking at students’ future goals and the relationship with motivation and engagement. We are examining whether or not there is a connection between this and how children organise their learning.”

> Click here to read Prof McInerney’s INSPIRE article

> Click here to learn more about this project